The dawn of gravitational wave science

In a handful of observatories in Europe and the US, scientists have been waiting and listening. Their quest was to detect gravitational waves - a rhythm of stretch and compression in the space-time fabric.

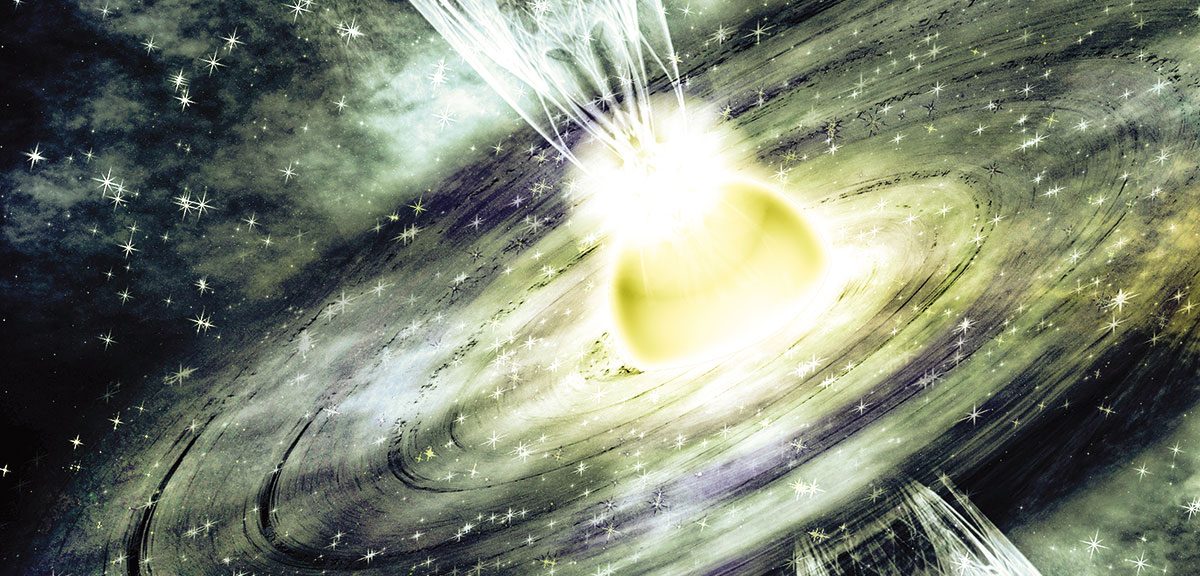

GRAWITON, funded under the FP7 Marie Curie Actions, has been a wonderful initiative that introduced a team of young researchers into the gravitational wave research. The initial training network contributed to groundbreaking discoveries that allowed them to see and hear the spectacular collision of neutron stars and of black holes.

This marks the first time that cosmic events have been viewed in both gravitational waves and light. Perhaps one day we could also see and hear other sounds of the Universe such as the frantic final moments in the life of other massive stars or even the remnant rumble of the Big Bang itself.

EINSTEIN’S UNFINISHED SYMPHONY

Powerful events involving massive accelerating objects, just like detonating stars or colliding black holes, disrupt space-time in such a way that waves of distorted space seem to be radiating from the source at the speed of light. These ripples alternately stretch and squeeze space, causing the distance between objects to expand and contract.

They permeate everything from the emptiest spot to the densest core of any object in the sky without requiring air or some other material to carry them. By the time they reach Earth, they are so faint that picking them out of the surrounding noise is comparable to noticing the removal of a single grain of sand.

These vibrations in space-time or gravitational waves are the last prediction of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. They had been, until recently, his unfinished symphony, waiting nearly a century to be heard. Given the scant experiments available at the time of its conception, general relativity had been side-lined from mainstream physics and largely became a theoretical curiosity. But from 1960s onward, evidence had grown for a Big Bang that set the Universe expanding and for black holes – two of Einstein’s key predictions.

FORTUNE FAVOURS THE BRAVE

The area of gravitational waves has been therefore one of those areas of astronomy research that has had a number of quiet times and rebirths. “The GRAWITON initiative was proposed at a time that gravitational waves used to be a research topic that had almost been pushed aside by most astronomers and had only been investigated by a small fraction of the global physics community – especially those involved in the US-based Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and the Europe-based Virgo detector,” notes project coordinator Michele Punturo.

Within two years, these detectors had made crucial discoveries that opened a new chapter in the workings of the Universe. Thirteen early-stage researchers involved in GRAWITON have been part of this epochal change in the history of astrophysics by making immense contributions to the detection of gravitational waves.

NETWORK CORE ACTIVITIES

Researchers stemming from France, Germany and Italy contributed to the data analysis and technological developments necessary for the breakthroughs. In particular, they had the opportunity to engage with complex optical apparatuses, high-power and low-noise lasers, highly reflective coatings, and simulation and modelling work.

Given that gravitational waves is a new and still unexplored field, they worked on simplifying data analysis methods. They used what they call ‘matched filters’ for detecting and analysing the presence of known signals, or templates, in unknown signals.

For modelling poorly known astrophysical sources, they resorted to other techniques; for example, they searched sources of excess energy with certain frequency behaviour. Yet, they left plenty of room for improving models for completely unknown sources of gravitational waves or more complex phenomena that are still not possible to be accurately described. New data analysis methods were also developed for coalescing binary black holes where templates are quite poor.

Furthermore, researchers received advanced training in the cutting-edge technologies that will be implemented in future gravitational wave detectors such as the Einstein telescope – a proposed third-generation groundbased gravitational wave detector, currently under study by some institutions in the EU. New lasers of a different wavelength and new laser injection optics developed by GRAWITON will be crucial to testing the general theory of relativity in strong gravitational field conditions and realising precision gravitational wave astronomy.

WHY GRAVITATIONAL WAVES MATTER

“The detection of gravitational waves has been much more than a simple confirmation of Einstein’s prediction. These ripples in the space-time fabric are revealing a Universe invisible to other messengers: the black-hole Universe,” notes Punturo. This has been invisible to scientists who have relied almost exclusively on electromagnetic radiation to study objects and phenomena in the Universe.

The observations of ten stellar-mass binary black hole mergers that have been confidently detected to date are posing new questions on gravitational wave astronomy that will help explore some of the greatest questions in physics: How do black holes form? Is general relativity a valid description of gravity so that it can rule out other theories that are often introduced to replace the role of dark matter and dark energy?

The gravitational waves observed from the neutron star collision gave a sense of what a neutron star might look like in its core. The information also helped researchers narrow down the possible origin of the Universe’s most powerful electromagnetic events – the short gamma ray bursts. Importantly, the observation solved a longstanding mystery about the origin of heavy elements such as gold and platinum.

The extreme weakness of all these sought-for effects demanded detection sensitivity of dazzling capabilities. “LIGO and Virgo interferometers can sense motions at the level of one-hundred-thousandth of the radius of a proton. The next generation of detectors will be ten times more sensitive,” notes Punturo.

NEXT STEPS

The next LIGO-Virgo observing run will commence in March 2019. Estimates suggest much more binary black-hole mergers and, hopefully, a few more binary neutron-star detections. Improving the distance along the arms of the interferometers should exponentially increase the number of detected cosmic events.

Once significant progress will be made on this, the next main issue will be to have enough human and computational resources to analyse all gravitational wave signals. Then, there will always be a possibility to discover something unexpected, such as exotic sources of gravitational waves (micro black holes), that will revolutionise how we will view the Universe and our place within it.