Research and entrepreneurship: the view from both sides.

Are you interested in moving from academia to entrepreneurship? Marco Masia, MCAA Vice-Chair, gives an entertaining account of his own transition and explains the very different expectations within the two sectors.

Every researcher knows how it feels to see puzzled faces after explaining his or her research interests. That face is clearly saying, “uh, this is how the government wastes my tax money”, or “ah, is this meant to be a job?”, or “does it take more than one day to figure it out? I thought this guy was smarter”. Since people tend to be polite, they instead ask, “so, why is it useful?”.

It is frustrating, right? And the frustration is even bigger, as you have patiently prepared your pitch trying to follow Einstein’s suggestion: keep it simple so that even your grandma can understand it.

I recently left academia to join the world of start-ups and I can assure you that I have prepared my pitch very well. You might be surprised to know that I see the same puzzled face when I am asked what my start-up is about. People with no experience of start-ups look at me thinking, “does he make a living out of it?”, or “does it take more than one day to make it? I thought this guy was smarter”. Since people tend to be polite, they instead ask, “so, will it be the new Facebook?”.

People do not have a clue about what a start-up really is. Do you?

A start-up is a laboratory where new ideas are tested. Just like in a research lab, there are measurements to be made, criticalities to look for, tests to run, results to understand. It’s surprising how many things research and start-ups have in common. Researchers apply a scientific method to test their hypotheses.

Moving from the research bench to the business bench.

In spite of the lab analogy above, working in a start-up is certainly different to working at the bench. Both researchers and entrepreneurs add value to society in distinct ways: the former, mostly by advancing knowledge; the latter by introducing new products that meet and satisfy the needs of people. Advancing knowledge is a slow process. The timescales of start-ups are at least one order of magnitude faster than in academia. People must take quick decisions and do not have the option of dwelling on one particular problem for a long time. Therefore, moving from one world to the other can be a shock at first.

Nonetheless, I think that many researchers have a precious skill that is of great use in a start-up: the ability to look at things from a different perspective. This is a process that starts with gathering information, disassembling and then reorganising it many times to find the right angle, from which everything becomes clear. This skill is exactly what is needed when running a start-up experiment.

My “experiment”

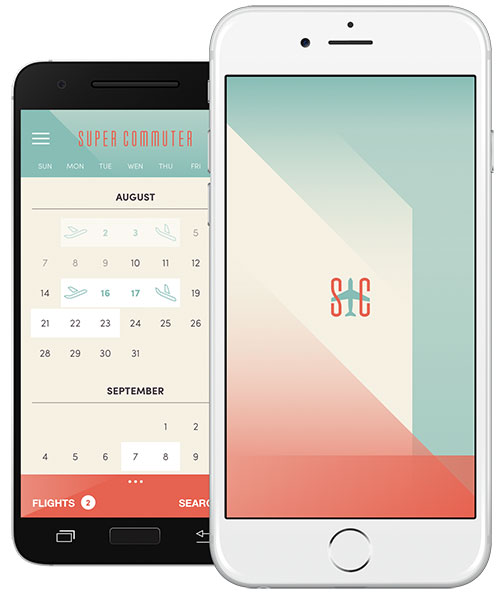

I have recently written a post on Medium about my transition from academy to entrepreneurship. My start-up is based on the simple observation that people who commute to work by plane every week are underserved by existing platforms. The idea is to make use of combinatorial theories to identify price saving solutions, and to

provide a travel booking engine that outperforms current online travel agencies… Hey! Please! Don’t give me that puzzled face!

The first app delivering such a service will be ready soon. Will it be successful? Will it pick up loyal customers quickly, or will it die off after few months? I don’t know yet. This is the experiment I am designing. And designing it has meant learning about the travel industry, the main stakeholders, the megatrends in travel technology, but also about communicating with a growing community of potential customers through a blog, Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn. It has meant making financial plans with different assumptions, and learning about the legal subtleties of running a business.

So, what if the experiment fails? Of course, I hope it doesn’t! But, if it fails, it is part of the game. Start-ups are known to be high-risk endeavors, and failure is accepted as one probable outcome. As in academia, I know that the ‘experiment’ might not work. Not all bright ideas are converted into a successful product.

Marco Masia,

Vice-Chair of the

MCAA

Start-ups develop a product testing their ideas about the needs of customers.This entails an experimentation phase to understand how they could deliver a unique service or product. This is why people are puzzled by what a start-up does: it’s the delivery of unknown services or products that they cannot easily grasp.

Here is a simple example: we all know how to add up numbers. Adding numbers in a row is the essence of the business model of a post office, or a super market. What if, instead of adding users sequentially, you place them on a spider web? You will get a social network! Isn’t it amazing? Just change the angle you look at things and you might become the next Mark Zuckerberg.

Start-ups are not about developing new knowledge (sometimes they do), but rather about finding an innovative way to use what we already know. It’s unbelievable how many great, successful products come from basic knowledge. All you need is ‘just’ to challenge common wisdom. This is why, with Horizon 2020, the European Commission has set out to boost innovation; we have

a lot of knowledge but not many smart ideas on how to use it.

Want to experiment with me?

If you’d like to know more about my business idea, please have a look at the company webpage. You might also want to follow me on Twitter, or check the social media pages of Super Commuter. Don’t hesitate to contact me if you have any questions or suggestions. Note that I am expanding the R&D department with projects ranging

from software development and engineering to geography, sociology and economics. If you are interested in forthcoming opportunities, have a look at this page.