News from the MCAA - Science Speaks All Languages: The Impact and Ignorance of Multilingualism

Newsletter

Globally, science needs and uses many languages for research to reach everyone. Yet, publications communicated in languages other than English get overlooked in assessments.

Introduction

Thinking, producing, using, and communicating in different languages broadens perspectives, enhances cultural sensitivity, reduces ethnocentrism, and advances local relevance and application of the body of knowledge. Multiple languages are needed to ensure broad access to research-based knowledge, interaction between science and society, as well as inclusive and diverse higher education systems. No single language can be the only language of science.

The World Speaks Many Languages, So Should Science

International publishing, projects, collaboration, and mobility have increased the use of English as the global lingua franca of science and education. Even if there are large differences between fields and countries, the use and appreciation of other languages in academia has diminished. Yet, with over 6,500 languages spoken globally, and large variations in foreign language skills, there is a need for production and transfer of knowledge in multiple languages. Europe alone has 24 official languages, and in 2016 one-third of Europeans aged 25-64 reported not knowing any foreign language.

The impact of research can be worldwide, but it is realized only locally in societies and communities where different languages are written and spoken. The application of both globally and locally produced knowledge requires critical discussion and dialogue between researchers and societal actors. In addition to the production of vast amounts of research published in English, the COVID-19 pandemic saw a widespread need for multilingual communication, not only between researchers, but also to reach and advise decision-makers, professionals, and citizens.

All Fields Need Multiple Languages

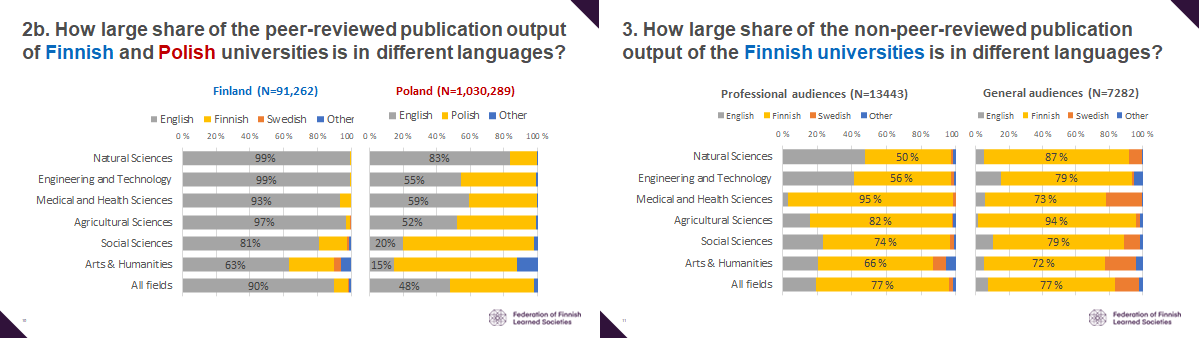

The whole range of national and local languages remain relevant for the social sciences and the humanities (SSH) scholars, whose focus on specific societies and cultures creates a need for publishing original results in the main languages of citizens who are affected by the research. Recently, Pölönen and Kulczycki (2023) compared Poland and Finland to discover that also science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) researchers maintain multilingual publishing strategies (see figure 1).

In Poland, over 70% of researchers in engineering, medicine and agriculture published peer-reviewed outputs in two or more languages, and nearly one-half of the universities’ output in these fields is in Polish. In Finland, almost all peer-reviewed STEM publications are in English, but the universities’ output from both STEM and SSH fields targeted to professional and general audiences is predominantly in the national languages.

Fairness in research assessment

Ideally, language is a non-issue in assessment. Researchers should be recognised and rewarded according to the quality and impact of their contribution. In practice, assessment criteria and methods are often far from language-neutral. International excellence is too often equated with English language publications, especially those in journals having an impact factor and indexed in the international Web of Science and Scopus databases. To many evaluators, research published in languages other than English and outside these databases remain invisible.

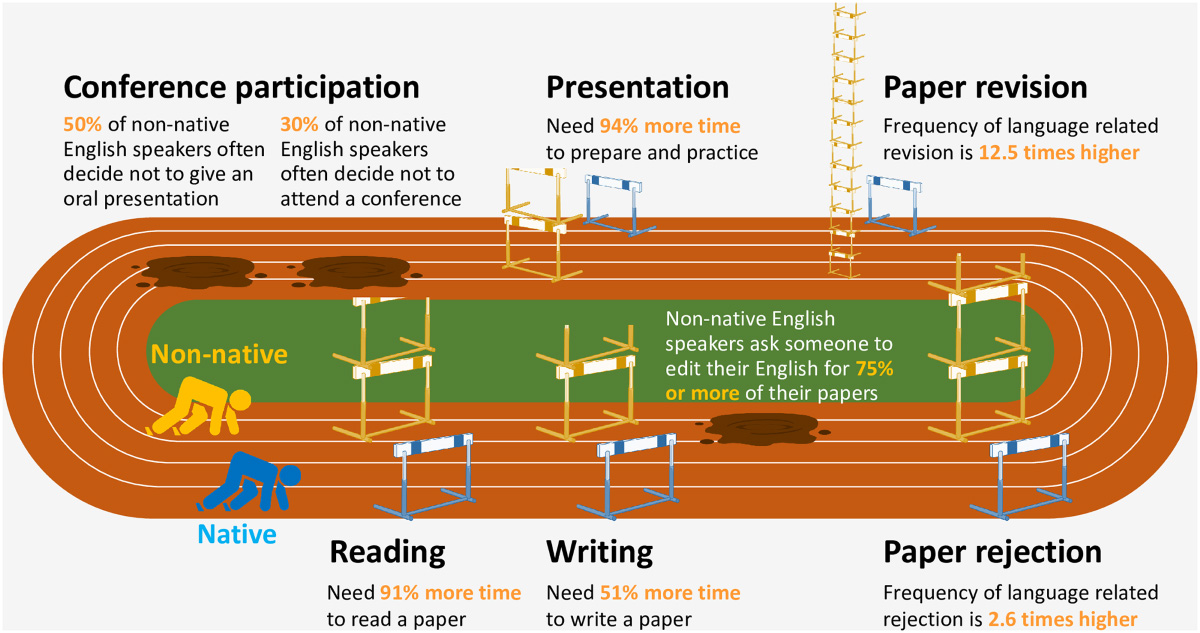

Amano et al. (2023) have shown how privilege of English language communication in science also results in severe disadvantages in scientific activities for second language speakers (see figure 2), especially to those with moderate or low proficiency. Compared to fluent speakers, they need more time and effort in reading, writing and revising publications and presentations, and may decide not to attend a conference or give an oral presentation. Such disadvantages lead to inequality in the career development of researchers from non-anglophone countries.

Time for Change

More than 600 organisations have already signed an international Agreement on Reforming Research Assessment, according to which, the diversity of contributions should be recognized “irrespective of the language in which they are communicated.” The Coalition for Advancing Research Assessment (CoARA), a community of the signatories of the agreement, will have a Working Group on “Multilingualism and Language Biases in Research Assessment.” The group was proposed by the Federation of Finnish Learned Societies in collaboration with over 30 partners, including the Marie Curie Alumni Association (MCAA) which will co-chair the working group (in the person of Gian Maria Greco). We look forward to the active contribution of the MCAA members in this work.

Janne Pölönen

Secretary General for Publication Forum

Federation of Finnish Learned Societies,

janne.polonen@tsv.fi

Twitter: @PolonenJanne

References

Amano, T., Ramírez-Castañeda, V., Berdejo-Espinola, V., Borokini, I., Chowdhury, S., Golivets, M., González-Trujillo, J. D., Montaño-Centellas, F., Paudel, K., White, R. L., & Veríssimo, D. (2023). The manifold costs of being a non-native English speaker in science. PLOS Biology, 21(7), e3002184. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3002184

Pölönen, J., & Kulczycki, E. (2023). Multilingual publishing across fields of science: analysis of data from Finland and Poland. In AILA World Anniversary Congress 2023, Lyon. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8162610