Special Issue - From waste to wealth: CIÊNCIAS’ journey to sustainable organic recycling

Newsletter

Launched in 2009 to raise awareness of permaculture, HortaFCUL is now a resilient community at the Faculty of Sciences in Lisbon, promoting nature-based solutions. Since 2016, the composting station has produced 47.95 tons of compost, serving as a successful neighborhood-scale composting project in Portugal.

HortaFCUL is a community-based permaculture project at Lisbon University’s Faculty of Sciences campus (FCUL) (Chaves and Vieira, 2020). Launched in 2009 by a group of students, its goal was to raise public awareness about innovative permaculture practices to address global challenges such as ecosystem degradation and climate change.

This bottom-up project has become a catalyst for practical and technical knowledge based on experimentation and scientific evidence. HortaFCUL is a resilient and inclusive community, educating the general public about nature-based solutions.

Some of these nature-based solutions include on-ground projects, such as three tiny forests, one edible garden, two agroforests, one vertical garden, and two composting stations.

Closing the waste loop

In 2016, the first composting station was installed in Permalab to process the organic waste from the campus’ gardens. The station consists of three compartments, each with a volume of 8m3.

Each compost pile is formed with alternate layers of “greens” (sources of nitrogen) and “browns” (sources of carbon), and it is transferred from one compartment to the next twice during the whole process to prevent excessive compaction, lack of oxygenation and increase feedstock homogenization (Horta, 2021). The period between the first piling and the compost sieving is, on average, 4 to 6 months.

A second station, installed in 2019, uses a vermicomposting approach. HortaFCUL utilizes eight 1.5m3 containers to process organic leftovers from the campus’ cafeterias and bars. Vermicomposting relies mostly on worm activity to catalyze organic matter transformation.

Worms aerate the substrate and enhance the availability of certain minerals. In HortaFCUL’s vermicomposting station, these macroinvertebrates should be added 21 days after the last input of organic matter, allowing the temperature to decrease to tolerable values for worms - around 25 ºC (Verhoeven, 2019). To ensure worm survival, containers are kept shaded. The liquid resulting from worm activity, also called worm slurry, is collected in buckets at the bottom of the containers and applied during crop growth.

Turning challenges into solutions

No community-led zero-budget project is free of structural challenges. However, permaculture teaches us how to turn a problem into a solution. Here are four challenges and their respective solutions:

Vermicomposting

Challenge #1: Major relative proportion of highly compactable and acidic residuals (coffee grounds and orange peels).

Solution: Alternating thinner layers of cafeteria’s residuals with thicker layers (3x thickness) of dry leaves. This prevents excessive compaction and subsequent fermentation, promoting feedstock oxygenation to boost microorganisms’ aerobic metabolism.

Challenge #2: Attraction of undesirable macroinvertebrates, e.g. cockroaches.

Solution: These macroinvertebrates become food for insectivorous birds, attracting native bird fauna.

Bionote

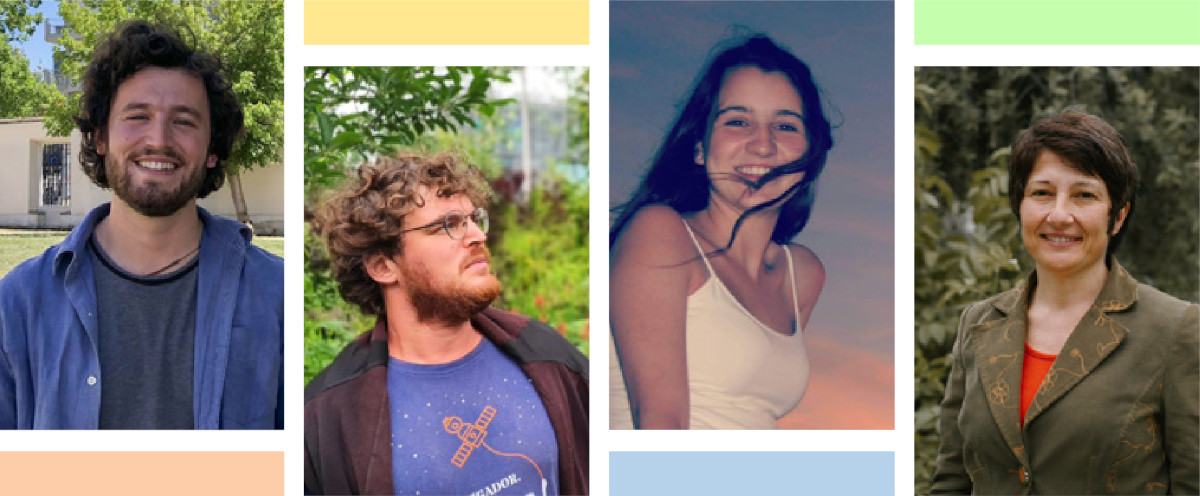

António Vaz Pato holds a Biology degree and an MSc in Conservation Biology from the University of Lisbon. His research focuses on restoration ecology and plant community responses in secondary succession, collaborating with CIBIO at the University of Porto. He also explores urban ecology and ecosystem services at HortaFCUL, University of Lisbon. Earlier this year, he authored a report on the 15-year impact of the HortaFCUL project, contributing to the research presented in this article.

Florian Ulm, originally from Germany, has lived in Portugal for nearly 14 years. He earned his Bachelor's in Biology from the University of Kaiserslautern in 2010 and a Master's in 2013, focusing on Acacia longifolia invasion in Portuguese dune systems. He completed a PhD in Biodiversity, Genetics, and Evolution from the University of Lisbon in 2019, researching practical solutions like using invasive species compost in agriculture. Florian has worked on projects such as R3forest and FightDesert, and currently works as a data scientist for 2adapt, focusing on climate change adaptation. He also promotes sustainability in higher education through the PermaLABs project.

Madalena Aires Horta holds a Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Biology from the University of Lisbon, Portugal, and a Master’s degree in Management and Conservation of Natural Resources from the University of Évora, Portugal. Her field of research is decentralized organic waste management systems in urban environments, and on this topic she has worked on a case study of a community-scale composting system in Lisbon. She has also worked professionally in this area, in Composta, a start-up focusing on composting systems in Cascais, Portugal.

Silvana Munzi, a biologist with a PhD in Environmental Science, has been a dedicated lichenologist since the 20th century. She participated in several projects on the impact of nitrogen on lichens and received an MSCA Marie Curie fellowship in 2012 to investigate nitrogen tolerance in lichens at the University of Lisbon. For five years, she was an Assistant Researcher there, studying symbiotic systems' molecular and physiological responses to environmental stresses. She also worked on biomonitoring pollution, climate change, and nitrogen stress in urban environments. Currently, she manages the ERC project "RUTTER: Making the Earth Global," focusing on nautical rutters.

Regular Composting

Challenge #3: High amount of coarse plant residuals (thick branches, vine plants).

Solution: Coarser residuals are deposited in swale ditches in Horta’s agroforests for faster biomass incorporation into the soil.

Challenge #4: Pile turning process relies solely on manpower.

Solution: Working days at Horta attract volunteers to assist with this demanding activity, promoting social bonding within the community.

Composting works

In permaculture, environmental, social and economic impacts are translated to three main ethics: Earth Care (environmental), People Care (social) and Fair Share (economic). Here are some compiled numbers (Vaz Pato et al., 2024):

Earth Care

• 47.95 tons of compost produced (2016 – 2023)

• 2.5 ha of green spaces as residuals’ regular source

• 8.1 tons of vermicompost produced (2021 - 2023)

• 3.04 tons of food leftovers recycled by vermicomposting per semester (2021 - 2024)

People Care

Compost production relies on community’s efforts; working days (450 at least since the project’s inception) at HortaFCUL are essential for promoting social bonding and integration near the members of this community.

Fair Share

Composting connects with the community through the Gift Table, where excess compost and plants are provided in exchange for a donation, following a Gift Economy approach. This method represents budget cuts by producing valuable goods with low financial input and avoiding residual transportation to landfills.

Fertilizing the ground

While university-led initiatives have been launched in the country over the past four years, they often lack production indicators and detailed descriptions. The HortaFCUL project, grounded in scientific knowledge and with a strong social component, provides a replicable example for other universities and institutions.

António Vaz Pato

Researcher

Universidade de Lisboa

vazpato@hotmail.com

Florian Ulm

Researcher

Universidade de Lisboa

ulm.florian@gmail.com

Madalena Aires Horta

Researcher

Universidade de Lisboa

madalenaayreshorta@gmail.com

Silvana Munzi

Researcher

Universidade de Lisboa

ssmunzi@fc.ul.pt

@MunziSilvana

References

Chaves, H., & Vieira, I. (2020). Um laboratório ao ar livre para criar biodiversidade através do trabalho coletivo – o exemplo da HortaFCUL. Alimentar boas práticas: Da produção ao consumo sustentável, 104-108. https://recil.ulusofona.pt/items/563cbe6b-256a-411a-8c41- 7f77a15848bf

Horta, M. N. F. A. (2021). Does community scale composting produce a viable outcome? Some physical and chemical properties of green waste composts produced in the Faculty of Sciences campus. Master’s thesis, Universidade de Évora.

Verhoeven M. (2019). From degradation to creation: closing the urban organic cycle. Internship thesis. HAS Hogeschool. https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/9ca444_ b07a851a80c047ed964f77df8708f90c.pdf

Vaz Pato, A., Ulm, F., Penha-Lopes, G., Sousa, M., Ribeiro, D., Haag, A., Rosa, I., Vicente, B., Avelar, D., Reynaud, R. (2024). Living the sustainable development: a university permaculture project as an ecosystem service provider: The HortaFCUL case study. Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa. https://ciencias.ulisboa.pt/sites/default/files/fcul/institucional/ higiene-seguranca/horta-fcul-report-2009-2023.pdf