Rebuilding bridges - Holding on to our Gantt chart in times of lockdown

Newsletter

How we transformed our home into a laboratory and managed to keep our dissemination activities alive.

The lockdown measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic was a challenging situation for all of us. But it entailed an extra effort in terms of adaptation for those of us who had to continue with experimental designs despite the inability to use the faculty’s facilities.

Reacting to the pandemic

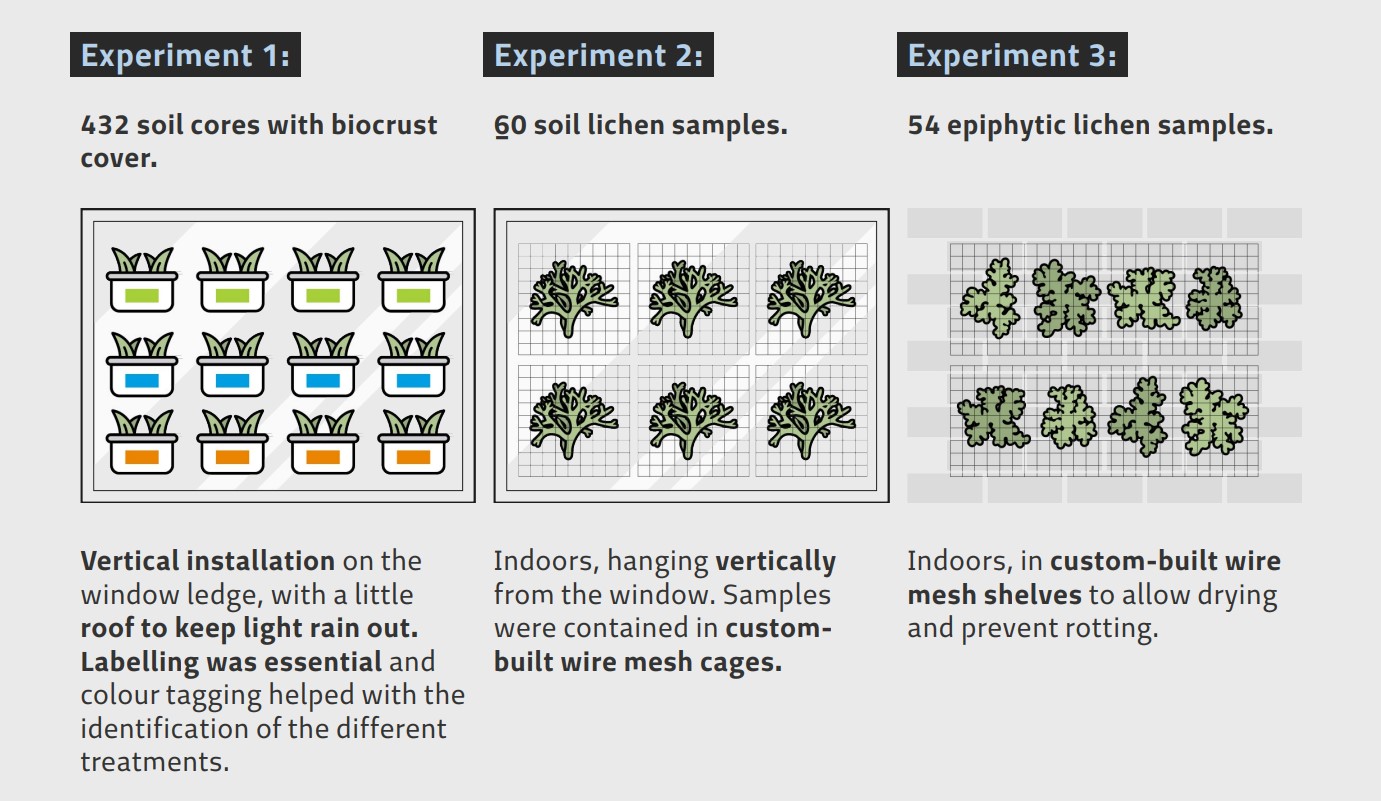

At the time of the outbreak, I lived in a small apartment in Lisbon, Portugal, with my husband (Javier) and my 3-year-old daughter. We had just returned from our sampling campaigns along a transect in the Mediterranean basin and a total of 546 samples belonging to three different experiments were waiting for their respective treatments at the faculty’s greenhouse. Most of these samples (432) were intact soil cores of 5 cm diameter with biocrust cover, but there were also 60 samples of soil lichens and 54 samples of epiphytic lichens attached to sticks and pieces of branches. The fact that our samples were live biotic systems did not allow us to postpone our experiments indefinitely, not to mention the temporal restrictions imposed by the Gantt chart of our MSCA project Med-N-Change. At that time, the pandemic had disrupted everyday life for people in China and Italy. In Portugal, however, we still had time to react. We considered the huge uncertainty regarding our ability to access the samples daily if they were placed in the faculty’s facilities. After assessing our options, we realised that we had no choice but to bring them home. Although it felt like some kind of mission impossible at the beginning, my husband and I managed to relocate all the three experiments into a 60 m2 apartment. This is how we did it:

Home experiments: Tips and tricks

The high number of samples was an important challenge, but it was not the only one. Our samples were subjected to different watering treatments that involved a lot of moving and reordering of samples, which was quite challenging in such a small space. Just like every other living organism, both soils and lichens needed to be incubated in well ventilated, dry and sun-drenched places that provide homogeneous conditions to avoid differences among samples due to asymmetries during the incubation. As there were not plenty of spots like this in our apartment, we needed to be creative.

This is how we managed to overcome these constraints:

- Think vertically: Space was a limiting factor, so we took advantage of the vertical dimension. We created wooden shelves for sample housing which maximised the use of the few suitable spots to place our samples.

- Follow the light: Photosynthetic organisms need light, so we set up our experiments as close as possible to the windows (in the case of experiment 3) or even attached to them (in experiment 2) to optimise light reception.

- Simulate outdoor conditions: To provide our samples with a healthy living place while we applied the corresponding treatments, we controlled aeration, avoided direct sources of heat and maximised light exposure.

- Order above all: Labelling and colour tagging was essential to keep track of each sample as their position was randomised every few days to ensure homogeneous conditions.

- Avoid precipitations: As rain would interfere with our watering treatments, it was crucial to avoid any source of humidity as much as possible. To do so, we installed a little roof to keep rain out and detachable transparent polycarbonate panels to cover them externally from rainy and windy conditions. Whenever rainfall was not expected, the polycarbonate panels were detached to allow natural aeration.

- Fans to the rescue: Four little fans on top of the soil lichen samples facilitated drying after watering treatments to avoid putrefaction due to excessive humidity.

- Prevention is better than cure: To prevent vertical contamination, samples watered with higher concentrations of nitrogen and/ or increased watering frequencies were placed at the bottom of the structure. This strategic placing would avoid potential leaking and contamination between treatments that would be very hard to fix.

Public engagement without physical contact

As for any MSCA project, public engagement was a cornerstone of our project too. We outlined a meticulous plan of great dissemination activities to be implemented during the action. Suddenly, none of this would be possible. When Silvana Munzi (my supervisor) and I first tried to address the issue, we really did not think we could successfully replace face-to-face activities with those online. However, looking back we feel that this exceptional situation forced us to develop new strategies that in the end led us to reach a broader target audience. Indeed, Silvana recently published an article pointing out that online events encouraged by this pandemic generally required less effort to organise than face-to-face ones and engaged more people, especially when recorded and made available online for a long time. Through the following activities, we did our best to avoid falling behind despite the adverse circumstances:

- We participated in every call for online dissemination in outreach activities that we were aware of, whether they were launched by the European Commission (European Researchers’ Night, Science is Wonderful, International Day of Women and Girls in Science), by national associations (Ecology Day) or by our institution (Researchers Day).

- I have been collaborating with a local Radio for the last two years, promoted by the University Pablo de Olavide. The programme is called “Sustainable World” and my section is “Singular ecosystems.” It is also available as a podcast.

- As frequently as possible, dissemination articles have been published: newsletter and website of the University of Lisbon and Naukas (a science-related website for the general public).

- We developed an educational video game that shows a simplified version of nature and that is meant to illustrate concepts such as biodiversity and ecosystem services. Players have to correctly match three columns to learn how the variables they represent are related.

- We also launched an interactive quiz with questions about climate change and lichens.

- The website of the project was created and has been regularly updated to disseminate information about the goal of the project, as well as news about our team of researchers and collaborators, and our public engagement activities.

- We made use of social media whenever possible, mainly Twitter, ResearchGate and Facebook. The latter offered me the opportunity of being the MSCA fellow of the week from 4-11 2021, and of keeping track of all kinds of activities promoted by the European Commission’s Education and Culture Directorate-General.

- Within the scientific scope, we virtually attended every online workshop and congress we could.

We learned that a good way to increase the potential to reach different audiences is to make your activities available in as many languages as possible and to adapt the concepts and vocabulary to both adults and children. The extra effort of working on parallel versions of your activity will pay off as citizens will receive your message in the best possible conditions which will promote an effective learning.

Although we deeply hope this situation triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic should never occur again, we are pleased to share these tips to help other researchers fulfil their projects in potential future constraints.

Lourdes Morillas

Centre for Ecology,

Evolution and Environmental Changes,

Universidade de Lisboa Portugal

lmorillas@fc.ul.pt

Javier Roales

Department of Physical,

Chemical and Natural Systems,

University Pablo de Olavide, Seville, Spain

jroabat@upo.es

Silvana Munzi

Interuniversity Centre on History of Sciences

and Technology & Centre for Ecology,

Evolution and Environmental Changes,

University of Lisbon

ssmunzi@fc.ul.pt