Special Issue - Science communication: Making research accessible - Language models for dyslexia accessibility: The good and the ugly

In a recent study, we found that language models can assist readers with dyslexia. However, their outputs pose several risks. The paper, nominated for the Best Paper Award at the 26th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2025), broadens our understanding of AI’s ability to generate dyslexia-friendly text.

Roughly 10% of people in the general population are affected by dyslexia (Roitsch & Watson, 2019), estimates suggest the figure may reach as high as 20% (Phillips & Odegard, 2017), making it one of the leading causes of learning challenges. While assistive technologies have long been used to improve reading accessibility, no research has yet systematically assessed how effectively language models (LMs) can produce dyslexiafriendly text that follows recognised accessibility standards. This article summarises findings from our recent study (Ilkou et al., 2025) and explores their broader significance, examining both the potential benefits and risks of AI-generated text. It discusses how such tools could foster more inclusive, evidence-based communication and education for millions of readers.

What is dyslexia accessibility in text?

A text is considered dyslexia-accessible when its design and formatting facilitate easier reading and comprehension. This accessibility is typically achieved by adhering to established guidelines that promote readability for individuals with dyslexia. Organisations such as the United Nations, the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) and Inclusion Europe with the support of the European Commission have developed accessibility principles that address the needs of people with dyslexia. Although there is no single, universally accepted standard for dyslexia-friendly text, publicly available and well-defined recommendations can be found in the Dyslexia Style Guide published by the British Dyslexia Association (BDA, 2022).

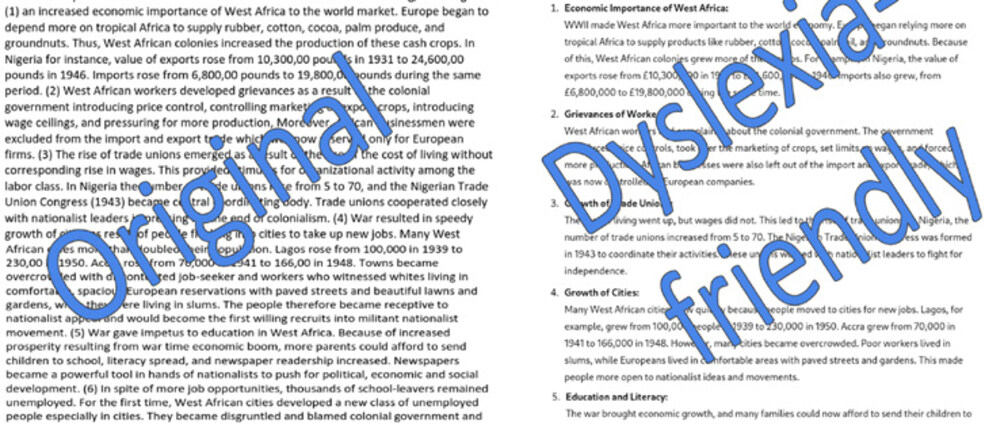

Below are two examples: On the left, the original text from a history textbook (West African Senior School Certificate Examination), and on the right, ChatGPT’s transformed dyslexia-friendly version of the same passage.

Can we trust AI on dyslexia accessibility for text?

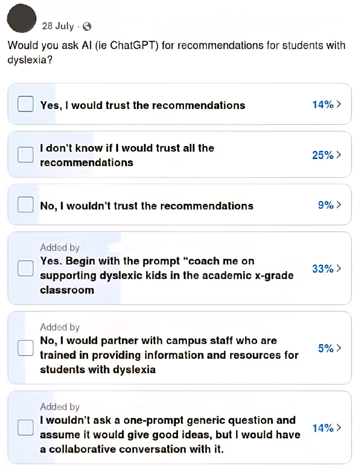

A Facebook poll of 122 users in the AI for Teachers group revealed strong interest in using LMs to obtain accessibility guidance, as shown below. Most participants indicated that they would use AI tools, such as ChatGPT, to receive recommendations when working with students with dyslexia. However, our findings indicate that the responses provided by the LMs require careful verification.

While some of the recommendations generated by the models could help mitigate potential risks, they must be applied with caution. For instance, the suggestion to ‘use positive language and encouraging messages’ may have unintended consequences if not paired with specific, constructive feedback (Lipnevich et al., 2023). This is particularly relevant for students with low self-esteem, for whom overly generic encouragement can be counterproductive (GrafKönig & Puca, 2024).

Similarly, the advice to ‘imagine you are reading the text from the perspective of someone with dyslexia’ may appear empathetic but could inadvertently reinforce labelling or lead to unintentional discrimination (Tunmer & Chapman, 2012).

On the positive side, all LMs showed statistically significant improvements compared with the original texts. The results indicate that the examined LMs consistently perform better when prompted with text-only criteria alongside the corresponding chapter, suggesting that structured input helps optimise their ability to generate accessible content. This broadens our understanding of what we can achieve with AI tools in education, opening new possibilities for generating accessible material for millions of readers worldwide.

However, when generating texts, findings also revealed a lack of sensitivity in language and tone. More critically, some problematic responses appeared in sections discussing colonialism and slavery generated by GPT-4-turbo. Even when considered individually, such incidents underscore the need to assess generated content not just for technical adherence to guidelines, but also for its accuracy and contextual appropriateness.

Final words

Special education continues to face stigma and societal prejudices about what individuals with learning disabilities, such as dyslexia, can achieve. Moving forward, the difference will lie in how the content is delivered, and we should normalise offering varied learning formats to suit different needs – just as we do with different kinds of cheese or chocolate.

Eleni Ilkou

TIB - Leibniz Information Center for Science and Communication

References:

BDA. (2022). Dyslexia friendly style guide: Creating a dyslexia friendly workplace. British Dyslexia Association.

Graf-König, N., & Puca, R. M. (2024). “Wow, you’re really smart!”: How children’s self-esteem affects teachers’ praise. Educational Psychology, 44(6–7), 749–764.

Ilkou, E., Alexiou, T., Antoniou, G., & Viberg, O. (2025, July). Dyslexia and AI: Do language models align with dyslexic style guide criteria? In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (pp. 32–47). Springer Nature Switzerland.

Lipnevich, A. A., Eßer, F. J., Park, M. J., & Winstone, N. (2023). Anchored in praise? Potential manifestation of the anchoring bias in feedback reception. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 30(1), 4–17.

Phillips, B. A. B., & Odegard, T. N. (2017). Evaluating the impact of dyslexia laws on the identification of specific learning disability and dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia, 67(3), 356–368.

Roitsch, J., & Watson, S. M. (2019). An overview of dyslexia: Definition, characteristics, assessment, identification, and intervention. Science Journal of Education, 7(4).

Tunmer, W. E., & Chapman, J. W. (2012). Does set for variability mediate the influence of vocabulary knowledge on the development of word recognition skills? Scientific Studies of Reading, 16(2), 122–140.